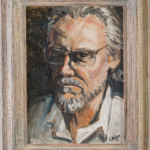

Tom Dunn (Photo: Patrick Clancy Photography)

Raised in Grand Forks and Minot, N. D., he left home to study chemistry at Purdue University in Indiana. “That didn’t last long!” he laughs. “I was from a long line of business folk and switched to management.” He moved to the Twin Cities in 1993 and got a job in Minneapolis at an insurance firm helping people settle claims on their homes after hurricanes, fires and earthquakes, as well as other things like hail damage.

“I enjoyed the job a lot,” he said. “You learn a lot of different skills but primarily I learned customer service from helping people in their time of need.”

He soon realized that photography was his “creative outlet and stress reliever.” He got his first camera at age 12 and went on to photograph friends and his travels throughout high school and college.

“Back then not everyone had mobile devices with cameras in them,” he quipped. After college, he came to the Twin Cities and “fell into” photography.

“Any time I had free time on the weekends I would grab my camera and hit the streets,” he said. “I realized I was happy with a camera in my hand.”

Ta-coumba Aiken mural, West 7th between Robert and Minnesota Street. (Photo: Tom Dunn)

Howl Berlin, 2017. (Photo: Tom Dunn)

Atlantic City, New Jersey. (Photo: Tom Dunn)

To hone his skills, he took photography classes at a local community college and the U of M. Then, in 1997, he met his mentor, the late Lowertown photographer Leo Kim, who had come to America at the end of the ’60s and had gone to school in Fargo, N.D. during the 1970s.

“Leo became my friend and mentor for about 15 years,” he said. “Leo taught me how to see things, how to see light and how to look at things differently. He had an architectural background, and everything had to be very artistic.”It was another love interest that attracted Dunn to Lowertown. He met his wife Colleen in 2005 and they married a few years later. She had lived in Lowertown for ten years.

“I found a studio space in the JAX building, sharing a space with two other artists, and started getting involved in the art crawl,” said Dunn. “I loved everything about Lowertown. It had such a bohemian feel. It was an artists’ enclave. It was like a secret place that no one knew about. There were still hardly any businesses at that time. Mears Park was evolving. Developers wanted to create an ‘urban oasis,’ a community that was a mixture of artists, residents and businesses.”

He has seen many changes to the neighborhood over the years and said it’s been troubling to see the gentrification that has occurred.

“The development that came later brought a ton of high rent apartments, and artists were displaced,” he said. “Seeing the art scene getting torn apart at the seams was difficult, not just for the artists but also for the people who had moved down here because they liked the scene. So many have left, and the neighborhood has become more homogenized.”

To help foster the art community, in 2010 Dunn got involved with the St. Paul Art Collective, which has been around since the 1970s. He joined as a board member and later served as president from 2013-2015.

“I was worried about balancing it with my commercial photography work and personal art and street photography, but I really wanted to work with the artists’ community,” he said. “The art crawl is a unique event, where you can see a lot of local art and artists in the spaces where they live and work, and it was always inspirational. What I brought to the board was my business background, and really started reaching out to local businesses asking them to support the Crawl. We tripled the advertising income that first year and planted the seeds for growth and sponsorship for future years.”

This success allowed the Collective to hire an art crawl director, giving the board more time to focus on supporting artists throughout the year rather than just the twice-a-year art crawl events. Under Dunn’s leadership, the Collective worked with The Show nonprofit and Midwest Special Services, founded in 1949 to support individuals with disabilities, to help them open The Show Gallery Lowertown, which today features artists of all abilities.

“I truly believe the Art Crawl needs to get more attention from the City, as the Twin Cities Jazz Festival does,” said Dunn. “The politicians and businesses need to celebrate that culture and promote the event for the sake of the artists, who this community was built on the backs of, who were here before anyone else was… If we lose the artists, Lowertown is just going to be an entertainment district with bars and restaurants, and for a vibrant neighborhood we need both sectors.”

Dunn is also well-known for his documentary photography project “Irish of Minnesota.” It began when one of his art-scene acquaintances, who was then a bartender at the Dubliner and was also involved with Public Art St. Paul, mentioned that the bar had space for an art wall. Dunn had just returned from a visit to Ireland and soon arranged to display photos from his trip.

Patrick O’Donnell, a meeting with whom inspired Tom’s Irish of Minnesota photo project. (Photo: Tom Dunn)

Through that opportunity, he met Patrick O’Donnell, who was on the board of the Irish Fair of Minnesota, the largest free Irish fair in the United States. O’Donnell told him that no one had ever documented the local Irish community. He gave him a list of around a dozen people to contact and asked them to sit for a photo portrait.

“I started there and almost five years later I have over one hundred portraits,” he said.

The minimalist, black and white, single light source portraits are gorgeous, and the scope of subjects speak to the diversity and size of Minnesota’s Irish community. In the 1857 census only 17% of St. Paul’s 9,973 residents were born in the United States. Those of Irish descent made up 10% of the workforce in 1880, and in 1895 accounted for roughly 5% of the city’s residents.

Daniel Corrigan. (Photo: Tom Dunn)

Thomas Whaley. (Photo: Tom Dunn)

Margaret Wachholz. (Photo: Tom Dunn)

Kieran Folliard. (Photo: Tom Dunn)

“I came to realize that the portraits were immigration stories,” said Dunn. “When the Irish first immigrated here they were not welcome, just as is happening today with different cultures. They were spat at and told to go home.”

It was a powerful and emotional experience for him to hear their stories.

“I asked those sitting to tell me their Irish stories and I then melted into the background,” he said. “They’re often brought to tears recounting tales of family members. The stories of joy and traditions have been truly magical. I hope that one day it becomes a book.”

Tom also appreciates a good road trip.

“I just turned 50 and for my birthday I drove down Highway 61 for a second time, photographing all the way. Highway 61 begins in Minnesota and goes all the way to the Mississippi Delta in Louisiana, connecting all these amazing communities and cities. It’s special to me because it literally follows the path of the Mississippi River. Eventually, this will become an exhibit and book.”

Old Highway 61 near Barnum, MN. (Photo: Tom Dunn)

Dunn has also taught classes for the last three years for FilmNorth, which helps artists tell their stories through video and other media. In June, he will teach a new class for the local nonprofit on street photography, his true passion. He also volunteers his photography services to Second Harvest Heartland, Youth Service Bureau and other community organizations. For more information, visit www.TomDunnPhoto.com.